Very Noyce: Phillip Noyce Talks Fast Charlie

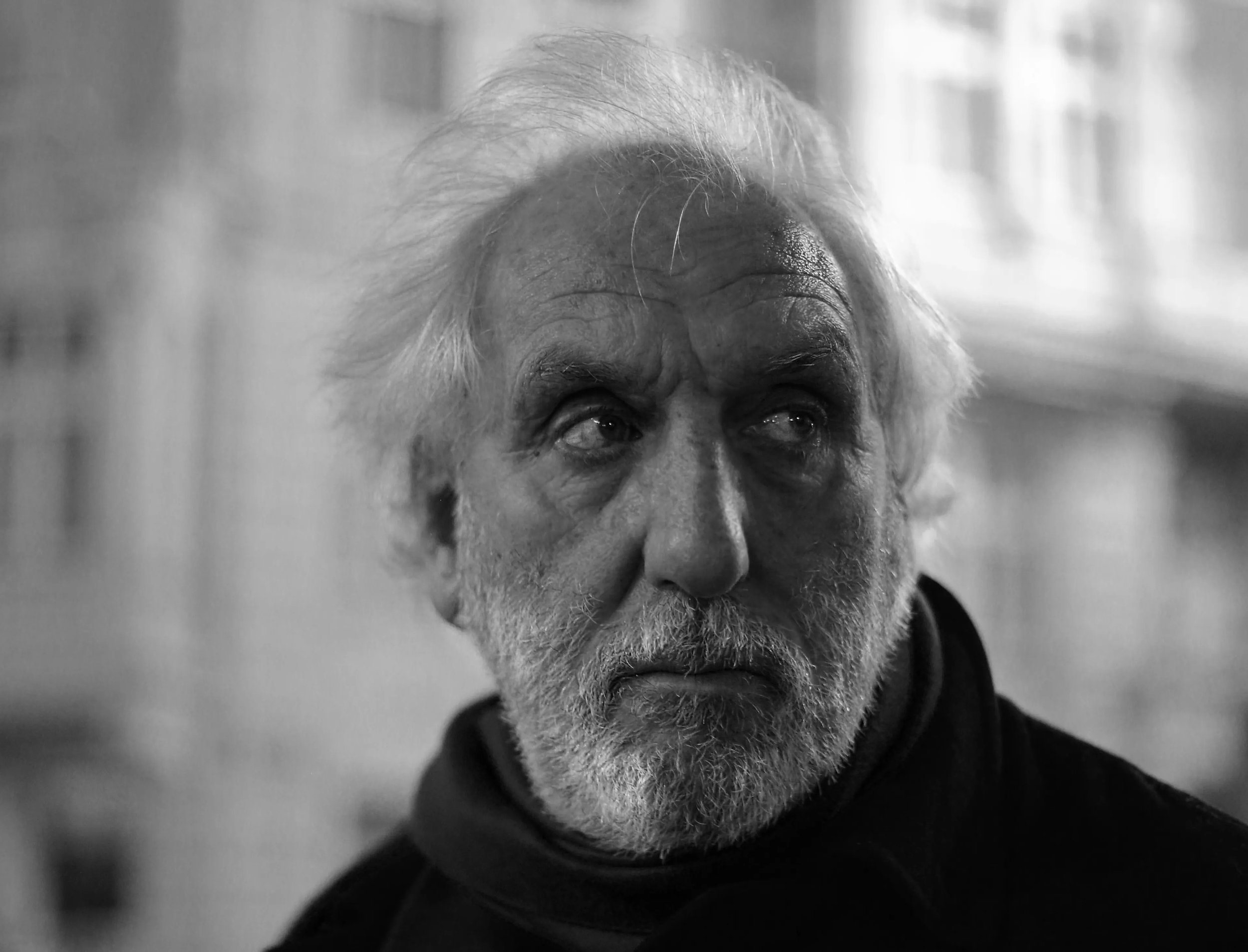

Photo: IF Magazine

Over an almost 50-year career, Phillip Noyce has rightly earned his place among Australia's greatest directors. For most, he was first recognised when he introduced a baby-faced Nicole Kidman in the seminal Australian thriller Dead Calm. The film received international acclaim, and at the tail end of the '80s, he became one of several homegrown talents to make the leap to Hollywood. Upon arrival, he quickly surrounded himself with commercial material and household names. He and Harrison Ford took over the Jack Ryan series with two top-notch adaptations. He also resurrected The Saint with Val Kilmer. And in the subsequent years, he demonstrated his range with works like The Quiet American and Rabbit-Proof Fence.

Now in his 70s, Noyce is still going strong. After some time away from features, he's helmed a handful of modestly budgeted thrillers. His latest, Fast Charlie, an adaptation of a Victor Gischler novel, continues his return to a smaller scale, but he has once again teamed up with a movie star. Pierce Brosnan plays the titular Charlie, a longtime fixer for a Florida mob boss. When a rival mobster tries to eliminate them and their crew, Charlie seeks revenge before leaving his life of crime behind. With extensive histories in the action genre, Noyce and Brosnan put their skills to good use. But with a darkly comedic tone, the film offered Noyce the chance to have some fun, and following many serious pieces, you can see he relished it.

To celebrate the film's UK release, Noyce told me about the liberation the film gave him, his memories of working with Harrison Ford, and the ease he felt knowing James Bond was in his corner. This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

DALTON: How did you become attached to Fast Charlie?

NOYCE: It was a script that the producer [Dan Grodnik] sent to me, which at the time was much more based on the original novel by Victor Gischler than the final film turned out. And I said, 'Yeah, it's a great story that I'd be happy to do as long as we could get Richard Wenk to write the script.' So it was the story and involvement of Richard Wenk that convinced me to sign on to it.

DALTON: Why did you want Wenk as your writer?

NOYCE: Richard has a macabre sense of humour. He writes great set pieces, but he's also able to write well-balanced, well-rounded characters. So he seemed like the perfect combination for this particular piece, which at its heart is very mischievous in the story it tells and the characters that are portrayed. Richard just seemed to have all of the potent possibilities in his writing, particularly those characters and set pieces he created for The Equalizer series.

DALTON: I was surprised by how funny the film was. I loved Charlie's line about his Ring doorbell and how the Donut character approaches his job, for example. It's been a minute since you've dabbled in comedy, how was it to re-explore?

NOYCE: Well, it has been a long time. Of course, there's been humorous moments in many films that I've made, although most of that humour was supplied by Harrison Ford, who is such a wonderful improviser. For example, in Clear and Present Danger, when he is trying to get a helicopter and says to the guy, 'Will you take a company cheque?' That was Harrison's line, not a script writer's.

I hadn't done comedy since 1989, when I made Blind Fury with the great Rutger Hauer. In between, I've made a lot of serious movies where a lot of people have suffered, been killed, run over, and met all sorts of demises. I haven't had a lot of fun with the movies I've made, and this was like getting out of jail because, with this movie, every day was a new tongue-twister of fun images and settings. It was a real liberation for me at this stage in my career.

DALTON: I thought Pierce Brosnan was fantastic as your lead. What made you think of him for the part, or was he already involved?

NOYCE: No, we approached him. He brings certain baggage, but in his case, good baggage from playing James Bond. He is also great at comedy. He's great at the one-liners, and he's great at the one eye, meaning he can twitch his eye and it's as eloquent as six sentences in terms of what it says to the audience. He's also great at drama. With Richard Wenk, the casting of the writer was because of the extremities of his potential, and the same applies to Pierce — he can handle action, comedy, and drama.

DALTON: Brosnan has such an iconic voice. Playing Charlie, it was interesting to hear him not mask it entirely but mix it with a Southern twang. Did the two of you discuss how the character would sound?

NOYCE: We worked with a dialect coach and came up with that accent. The responses from audiences have been varied. Some people say, 'Oh, that's not a genuine Southern accent,' and others say, 'He hits it perfectly.' Interestingly enough, it's the Southerners who say he hits it perfectly, and it's the Westerners who claim to be experts on Southern dialects (laughs). Of course, I hope [audiences] get the impression that he grew up in New Orleans from the photographs of him in that apartment in the French Quarter. And the funny thing is that a New Orleans accent is almost no accent. It's closer to New Jersey than a Southern accent. A Louisiana accent is quite Southern, but a New Orleans accent is quite neutral.

DALTON: Morena Baccarin was equally impressive. She and Brosnan had a very believable chemistry. Am I right in thinking their relationship is another differentiation you made from the novel?

NOYCE: Yeah, very, very different. In the novel, they climb into bed within 30 seconds of meeting each other, and they're in and out of the sack throughout the story (laughs). We thought it would be more tantalising for the audience if the two of them didn't even touch throughout the movie, but they touched each other internally. It was also because, of course, Pierce is not a spring chicken. When I cast Morena opposite him, it felt like we would be pushing the age difference too far if we followed Victor's ideas in how the relationship develops. So this is a relationship that reaches boiling point without getting under the sheets, and that's what's interesting about it. You project forward to the future at the end of the movie and imagine them together, but you're not faced with rejecting their coupling during the movie.

DALTON: I heard Baccarin joined quite late.

NOYCE: As late as you could. I mean, it was down to the last 10 seconds. We had run out of material to film without her. She came, I think, at the beginning of the second week. We filmed all week, not quite sure who was going to turn up or if someone was going to turn up. She came straight to set, and we talked to her during the previous week, but I didn't know how [she and Pierce] were going to interact with each other. Her first day was full of nervousness from all sides — from her, from me, from Pierce — but they just clicked together.

DALTON: The film had to deal with financing issues just prior to shooting. Did that impose any limitations on the production? Did you have to remove or work around certain story elements?

NOYCE: It didn't affect story elements, but it did mean we had to cut things, and what we cut was mainly action sequences. It forced the film from being a great big action package to being mainly about character interaction with a good measure of, hopefully, wonderful action set pieces. It changed the weight of the storytelling because some of those big action sequences went on for days, even weeks, of shooting as planned. But then a whole lot of the money just collapsed. About a week before we were due to start shooting, we lost our original actress, who shall remain nameless. The production was in turmoil for about five days as we tried to regroup and work out how much money we had and what we were going to do with it.

Fortunately, I had two amazing wingmen: Pierce on one side, Richard Wenk on the other. Pierce is as cool as a cucumber. He's been there so many times before, and Richard Wenk just loved the idea of a challenge, and that continued throughout the shoot. I'd email Richard at night and say, 'Richard, I've got 10 pages to shoot tomorrow, I can only shoot five, these are the scenes.' I'd wake up at 4am, as one does when shooting a film, and there would be an email reducing the 10 pages down to five that were shootable, told exactly the same story, and allowed me to achieve what I needed to achieve in the 12 hour day that I had at my disposal.

This is an interesting little piece of trivia that people might enjoy to know. At the beginning of the film, there's 26 executive producers listed. Remember that? It goes on and on and on. Well, those are all the angels that came to our help when the money fell through. We sent out distress signals up and down America, and the 26 people who answered the S.O.S. earned themselves executive producer credits. They gave us the money that allowed us to finish the movie. That's a story from the new era of independent filmmaking.

DALTON: Speaking of independent filmmaking, I read that back in the '70s, you would host screenings of short films from filmmakers like Peter Weir, George Miller, and Gillian Armstrong on the top level of a Sydney socialist bookshop when they were young up-and-comers. Could you tell me about that?

NOYCE: Well, you've grown up in a very different Australia in terms of moviemaking than the one I grew up in. You take for granted that you can see Australian films and stories delivered in the Australian accent. When I grew up, that was impossible. There was no Australian film industry to speak of. There were a few films that came and went. They were mainly English productions like Smiley Gets a Gun or Robbery Under Arms, but we didn't have a film industry. There was no economic need, in a way, to have one because the Americans made the films and owned the cinemas and those that didn't were owned by British interests. Australians also suffered from a dreadful disease at the time, which was called the cultural cringe. It was a disease that gripped a sufferer and convinced them when they looked in the mirror that they need not bother to make movies or write plays or write poetry or write novels because we were not good enough. The Brits can do it better, so why bother?

So we baby boomers were determined to make movies, and we started making shorts. We couldn't get them screened, so we just set up our own cinemas at the top of bookshops, in rooms at universities, wherever we could. And we found that Australians wanted to see themselves because Australians were like babies looking in the mirror — 'Oh, my God! That's me! Wow! Wow! Wow!' (touches face). So the short movie screenings were incredibly successful. We started with one cinema, one session a week, and pretty soon, we had seven filmmaker cinemas running seven days a week, three sessions a day. They were all illegal, but the audience wanted to see themselves and look in that mirror and hear their voices. And it so happened that the people who screened their movies at the filmmaker cinemas went on to be what we call the New Wave of Australian film directors — Peter Weir, Bruce Beresford, myself, Gillian Armstrong, George Miller, Paul Cox, and on and on and on.

DALTON: You recently participated in a documentary about your life and oeuvre. How did you find that experience? And what should audiences expect?

NOYCE: Listen, that documentary has been going on for about 20 years, so I've lost track of what they can expect to see (laughs). It's just been filmed in bits and pieces whenever I'm in Australia or when they come [to Los Angeles]. I haven't seen the movie; they're editing it at the moment, so I'm not sure what they'll choose. But it does go all the way back to when I was in my mid 20s at the filmmaker cinema at film school. It examines my life's work, I believe. But I'm not the director, so whatever the director [Ted McDonnell] wants to do with the footage, he will do.

DALTON: I cannot wait to view it. As a fan of your work, sir, it has been a pleasure talking with you this morning. I will close out by saying the boat chase in Patriot Games is absolutely sublime.

NOYCE: You know where a lot of that was shot?

DALTON: Where?

NOYCE: In the parking lot of Paramount Pictures! Seriously! It's where Cecil B. DeMille parted the Red Sea [in The Ten Commandments]. There is a sort of swimming pool there, and we built up the sides and created waves. All the close-ups of that boat chase were shot in the car park with the illusion of movement created by sweeping water past them fired by firefighters with huge hoses, so it appears that they're moving. Of course, we intercut it with second-unit shots taken out at sea, but it's mainly right there in the car park!

This article was originally published by FilmInk